In one of the earliest accounts of social distancing in Singapore, a 1901 newspaper report titled “A Case of Plague” tells of a ten-year-old boy who succumbed to plague at a quarantine camp. After the confirmed presence of plague bacteria, the house in which he lived and its adjacent quarters were cleaned and isolated. The remaining residents were sent to a quarantine station on St. John’s Island.

Popularly referred to as quarantine, this practice can be traced back to as early as 600CE. It gained currency during the plague epidemic in 1348 in Venice, during which ships carrying cargo and travellers to the major seaport in Italy were detained in the lagoon for forty days.

This practice of distancing, for the most part, was abolished with the production of antibiotics and vaccines. Recent outbreaks such as SARS and COVID-19, however, have necessitated new modes of distancing and quarantining being adopted to protect both the individual and collective body.

This section examines three images related to the quarantine practices on St John’s Island.

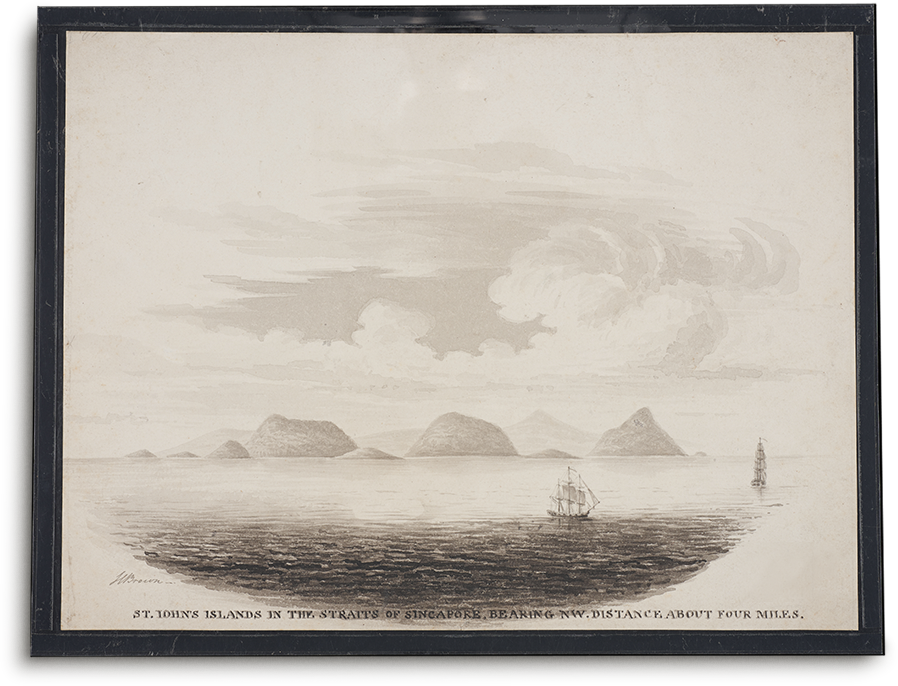

Drawing titled

“St John's Islands in the Straits of Singapore,

bearing NW distance about four miles”

Except for its detailed caption, this impressionistic image does not reveal much. A closer look reveals the ships in the foreground, which likely received much attention upon their arrival to Singapore in the early 19th century. Travelling from faraway places, the ships and their passengers were often carriers of infectious diseases, and ports functioned as control zones to restrict the influx of such illnesses.

Captain James Brown | Early 19th century | Wash on paper | 22.5 x 29.5cm | HP-0070

A cholera outbreak in the 1870s led to the building of an attap-roofed lazaretto (quarantine station) on St John’s Island in 1874. That same year, the British ship the SS Milton arrived at the island with some 1,300 cholera-stricken Chinese coolies on board. St John’s Island soon gained a reputation as a quarantining station, which expanded in terms of facilities and personnel. By 1930, the facilities on the island were used to screen both immigrants and pilgrims returning from Mecca. The island later became home to an opium treatment centre (1955−1975), where patients received treatment and rehabilitation, and were trained in several skills to help them re-integrate into society.

Postcard titled “St John’s Island”, Singapore

This coloured postcard shows immigrants with their belongings at the port on St John’s Island. From the 1900s, thousands of passengers and crew members passed through the island each year, where they were screened, tested, quarantined and treated before being sent to Singapore.

c1908 | Hand-coloured postcard | 13.6 x 8.9cm | XXXX-00384

The island was fully equipped as a quarantine station by the 1930s, according to a 1935 account of the extent of work carried out. Even while praising the natural beauty of St John’s Island, a correspondent provides a detailed tour of its medical facilities − modern storehouses containing sulphur used to fumigate ships, muster sheds for changing clothes, and showers for the immigrants. The discarded clothing and belongings went through steam disinfectors for 25 minutes. Some 6,000 people were housed in 22 camps and there were hospitals for treating smallpox, cholera, plague, chickenpox, measles and similar diseases. The island also had a dispensary and a laboratory, with sufficient vaccines stored in cooling chambers. Regular health bulletins provided information on the diseases in various ports. The writer estimates that at the time of writing, some 8 million people had been examined over the past 20 years, and about 2,000 ships were disinfected annually by two dedicated launches fitted with special apparatus to fumigate ships.

Petition letter and envelope

This petition letter was drafted and signed (by stamp) by about 150 to 200 representatives of the Singapore Chinese merchant community in 1906. It pays tribute to the significant contributions of Mr Sun Shih Ting, who served as Chinese Consul to Singapore (January 1906 to October 1907), and petitions for the extension of his tenure in Singapore.

1906 | Paper | 26.7 x 13.7cm

Letter | 23.5 x 117cm | 2011-01059-001;

The letter notes that Mr Sun was instrumental in convincing the colonial authorities to abolish the practice of making incoming Chinese migrants strip naked on board the ships for health examinations. The letter also mentions the practice of requiring incoming Chinese migrants to be quarantined at St John's Island.

The petition seems to have been successful, with Mr Sun staying on for about a year before eventually returning to China to attend to the burial of his mother.