Catchy songs and ditties have long been used to teach children to cultivate healthy hand-washing habits. This practice has seen a resurgence in recent months, with experts advising that adults and children alike should spend no less than 20 seconds – or the equivalent of humming the “Happy Birthday” song twice – to soap and rinse our hands in order to prevent the accidental spread of the COVID-19 virus.

While personal hygiene is important, it is equally essential to keep our environment clean to reduce the risk and spread of infections. The introduction of planned living and common areas, piped water, good sanitation and waste disposal, among other initiatives, has gone a long way towards promoting public health in Singapore.

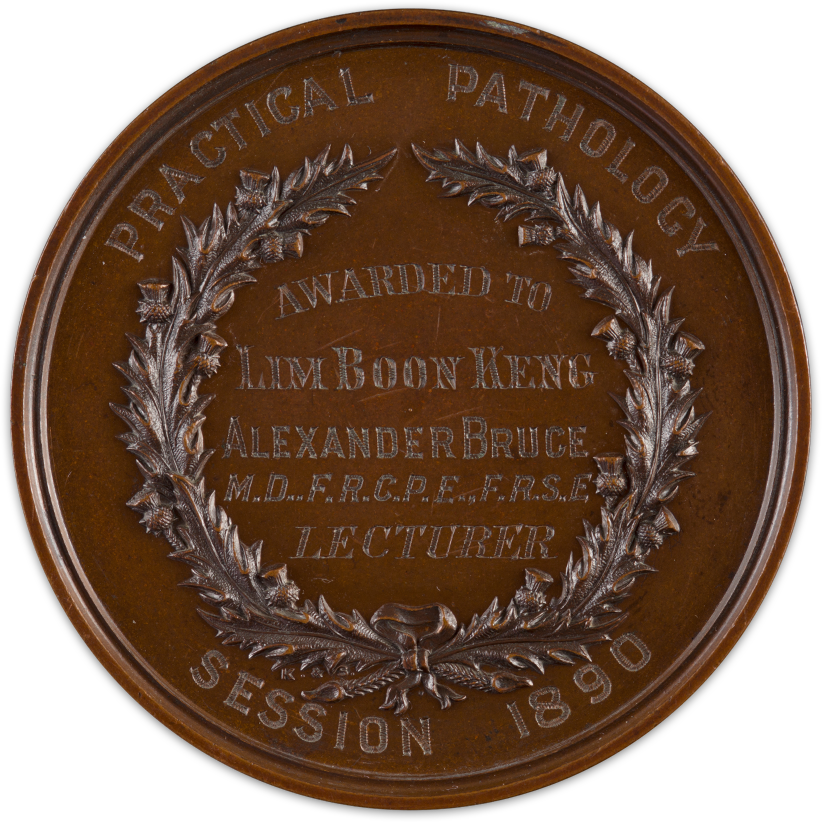

This section explores the contributions of Dr Lim Boon Keng, one of Singapore’s pioneer social reformers, as well as the role of playgrounds and public campaigns in helping people in Singapore to cultivate good hygiene habits that safeguard public health.

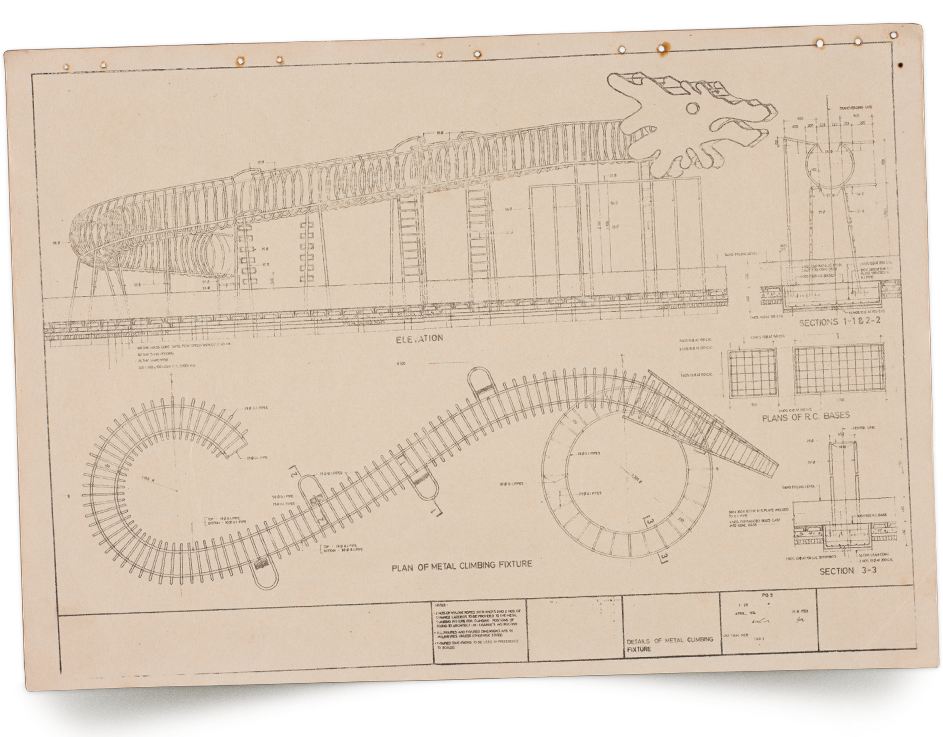

A playground prototype drawing by Khor Ean Ghee

This drawing shows the blueprint for a metal dragon playground that was located in Toa Payoh Town Garden in 1975. The structure was later modified to include decorative mosaics, see-saws and swings, among others. The popular dragon motif was also often adopted for other playgrounds.

1970−1979 | Paper | 29.8 x 20.6cm | 2014-00977-012

Khor Ean Ghee (b.1934), who designed this familiar icon, worked as an interior designer with the Housing and Development Board from 1969 to 1983. Playgrounds featuring local designs such as these were provided alongside public housing as dedicated shared spaces for children and families.

Postcard titled “Playground Centre at Toa Payoh Town”

This coloured postcard features the playground and garden in Toa Payoh with its fish pond and viewing tower. On the back is the description “beautifully landscaped Toa Payoh Garden provides a healthy recreational ground for the residents of this satellite town”. The garden was closed in 1999.

1970s | Postcard | 10.5 x 15cm | 2008-04307

Toa Payoh was the second town to be developed by the Housing and Development Board (HDB) in 1960. In November 1972, the HDB announced plans for the construction of the Toa Payoh Town Gardens as part of the revamp of the new town, which was to be the Games Village when Singapore hosted the 7th Southeast Asian Peninsular (SEAP) Games in 1973. Plans for the gardens included a children’s playground, an artificial forest, and a man-made lake complete with waterfalls for fishing and boating activities. The Toa Payoh Sports Stadium was another facility that was built in the area especially for the games.

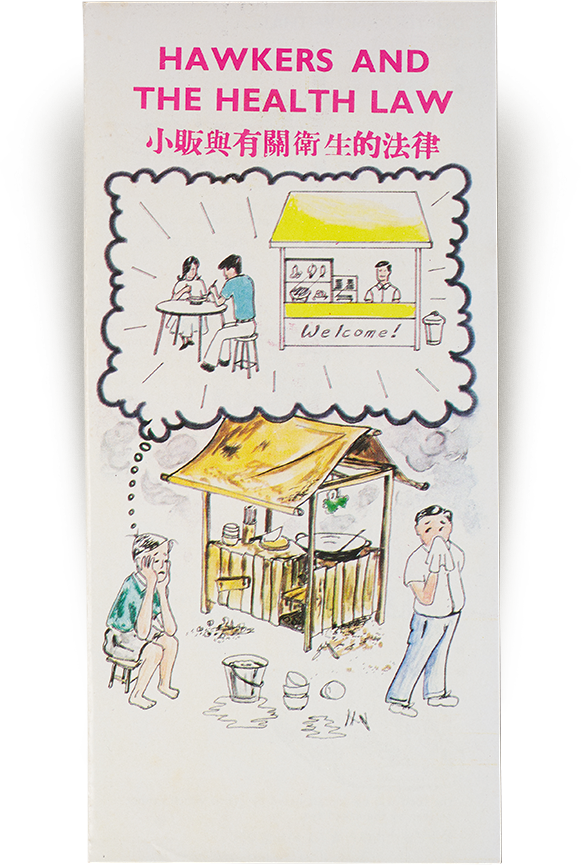

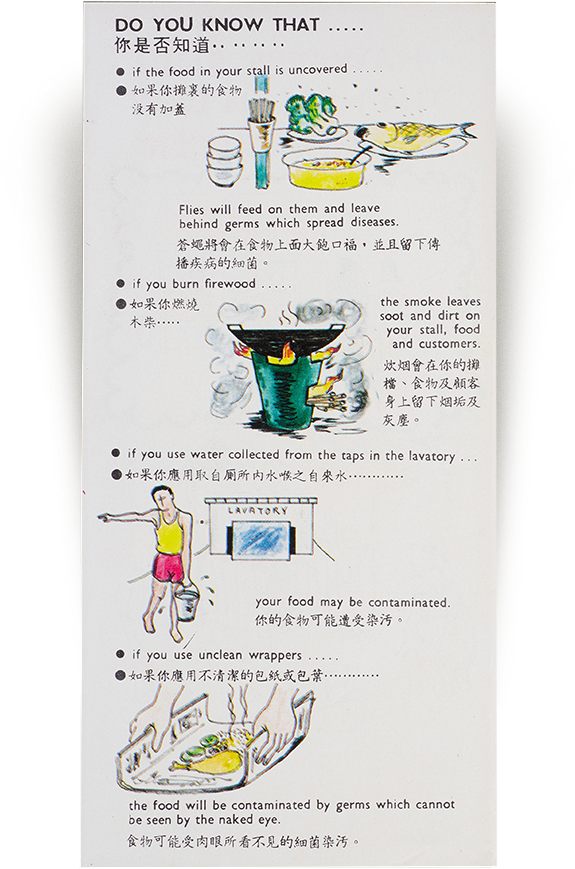

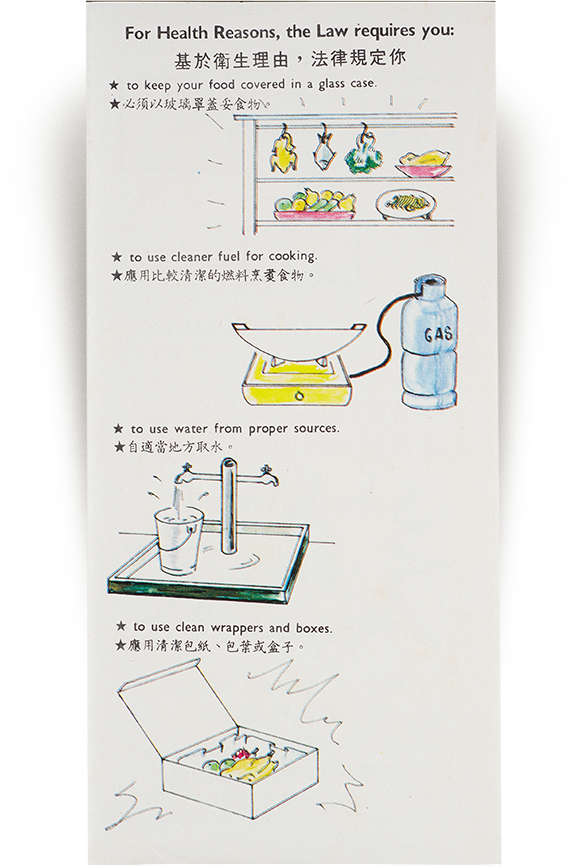

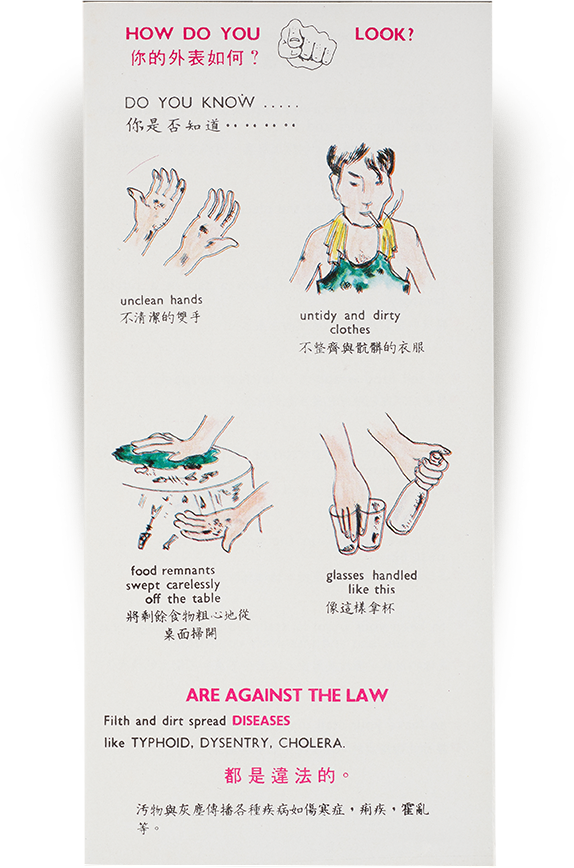

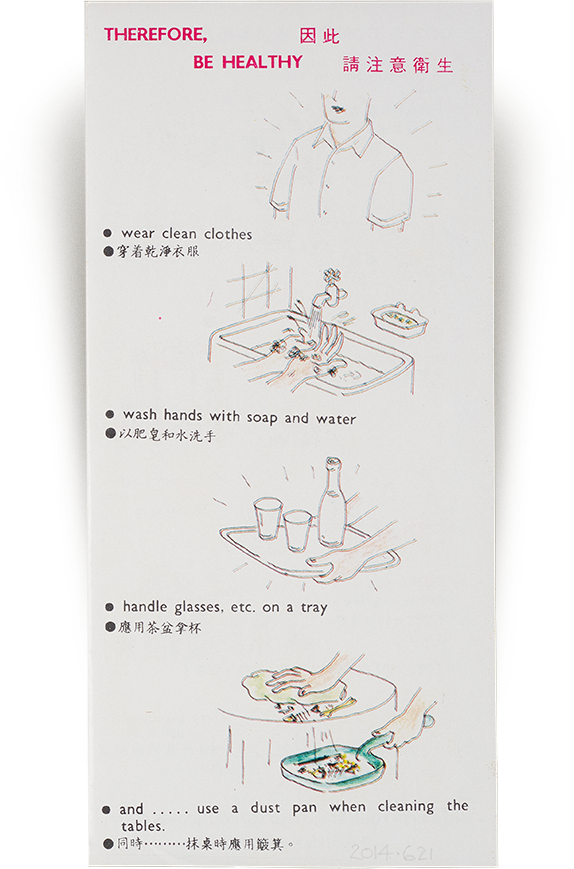

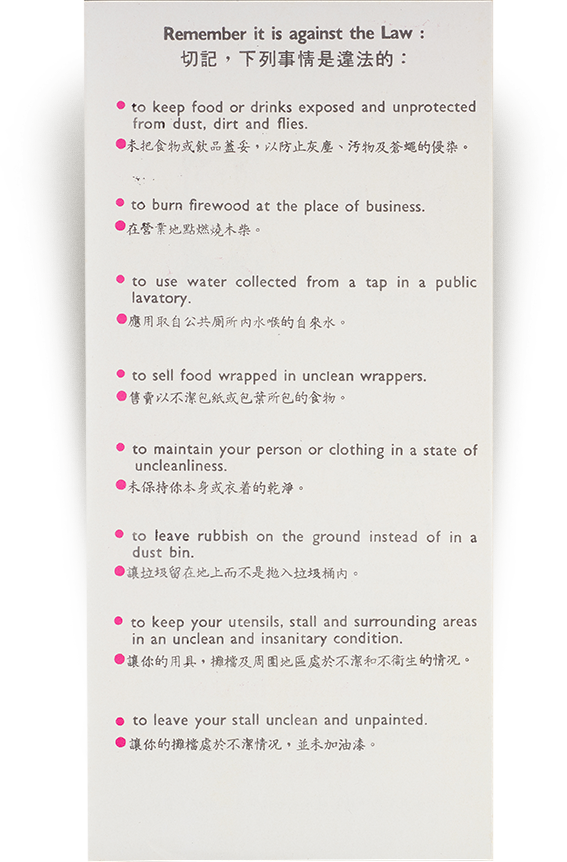

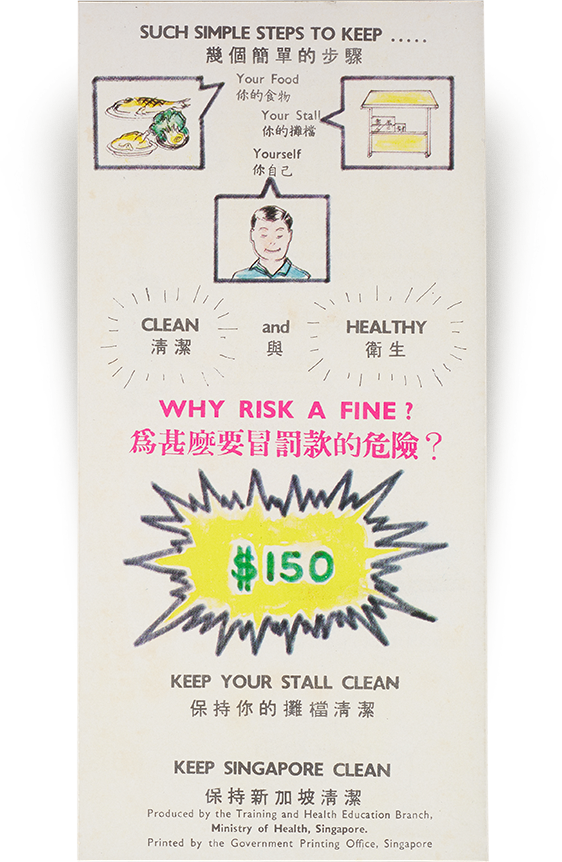

“Hawkers and The Health Law” booklet

Between the early 1970s and 1980s, Singapore food vendors relocated to hawker centres as part of the government’s efforts to promote public hygiene and keep Singapore clean.

1980s | Paper | 21.8 x 41.2cm | 2014-00621

This illustrated 1980s booklet marks the government’s efforts at promoting public hygiene to hawkers, especially against gastro-intestinal infections such as cholera, dysentery and typhoid. It includes instructions on maintaining good hygiene and a clean environment, as well as information on the penalty for failing to adhere to the suggestions.

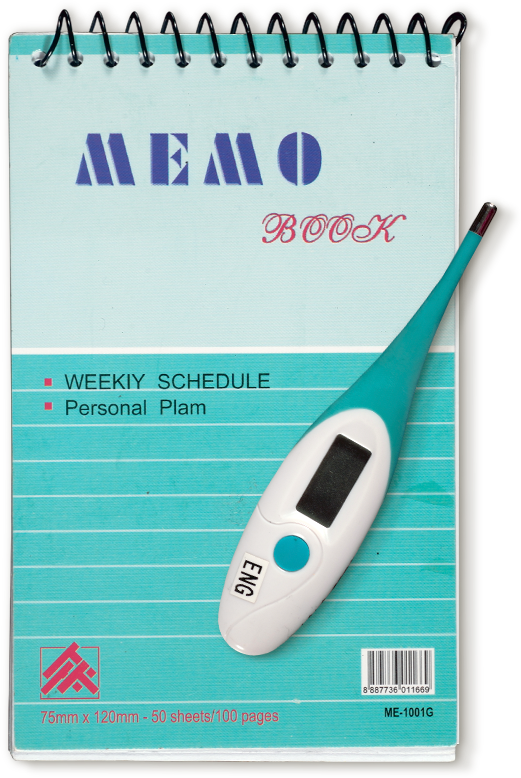

notebook and Thermometer used to record temperature during the SARS outbreak

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), the highly contagious viral infectious disease, broke out in Singapore in early 2003. SARS was caused by the SARS coronavirus. Like COVID-19, it caused breathing problems, with the infected developing a high fever with chills.

2008 | Paper | 12 x 7.5 x 0.4cm | Gift of Low Jyue Tyan | 2008-06991

2008 | Plastic | metal | 2.6 x 11.2 x 0.8cm | Gift of Teh Eng Eng | 2008-06989-002

People were encouraged to monitor their temperatures regularly, as illustrated by this thermometer and log book. Other measures implemented at the time, which seem very similar to the ones practised today, included wearing a mask, covering one’s face when coughing, washing one’s hands regularly, and keeping a clean environment.