The COVID-19 virus that has afflicted millions globally has made us acutely aware of the fragility of our bodies, and ignited a race against time to find a cure. Attempts to develop vaccines to shield ourselves against the infection continue to be made across the world.

Restoring the weakened body to health can be a long process, involving complex systems of both medical and non-medical practices. While hospitals and clinics dispense prescribed medicines and medical halls offer traditional alternatives, home remedies passed down over generations are still believed to help in recovery and prevent illness. Ranging from bracing herbal decoctions to tisanes brewed from condiments found in the kitchen pantry, these remedies are part of our shared knowledge.

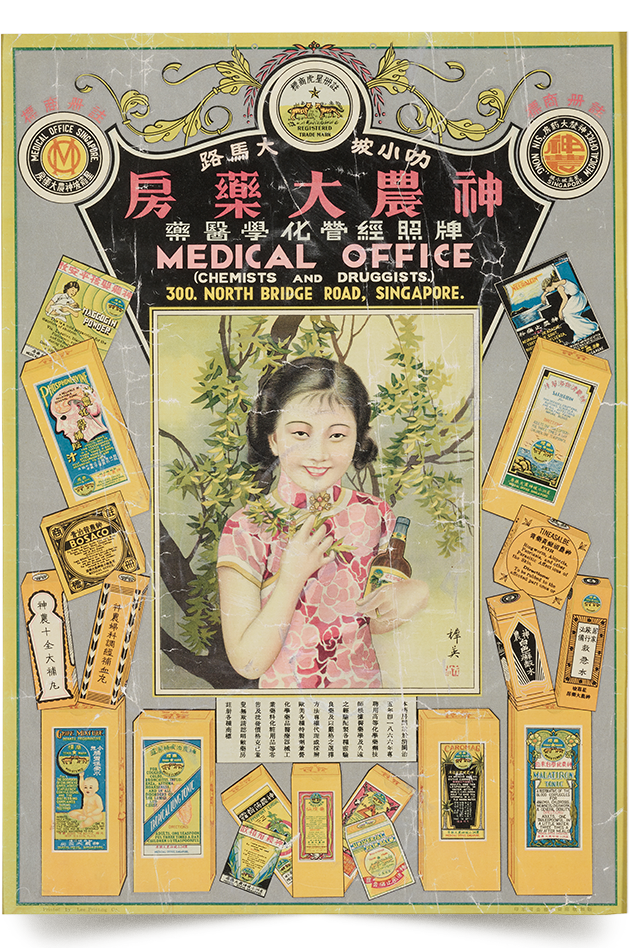

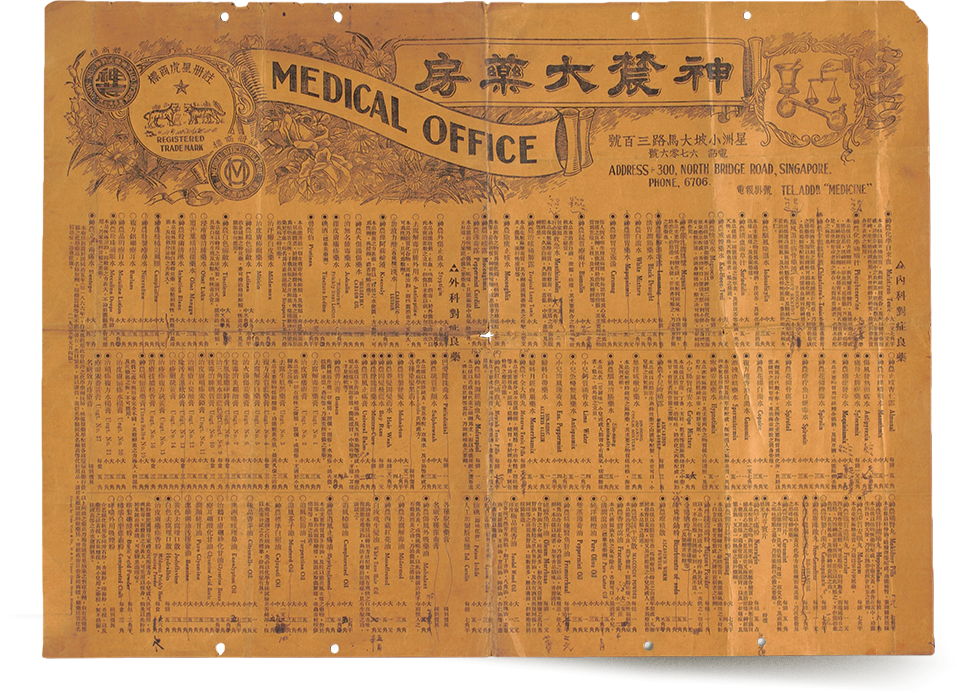

This section showcases several images related to early hospitals and medical halls in Singapore that played a major role in helping the sick. It also features non-medical options that have been used to restore one’s health over the years, some of which are still available today.

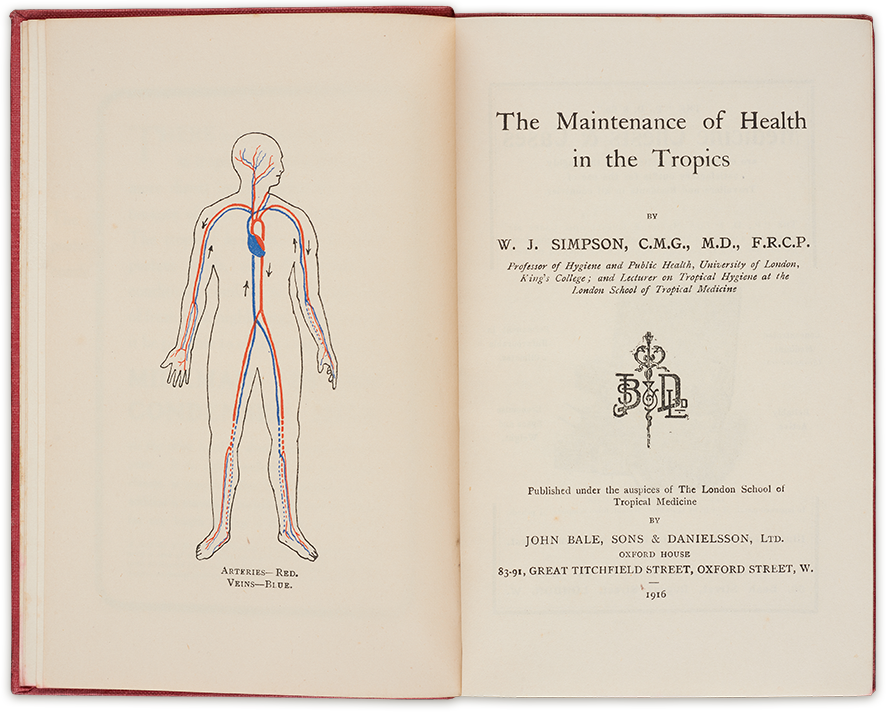

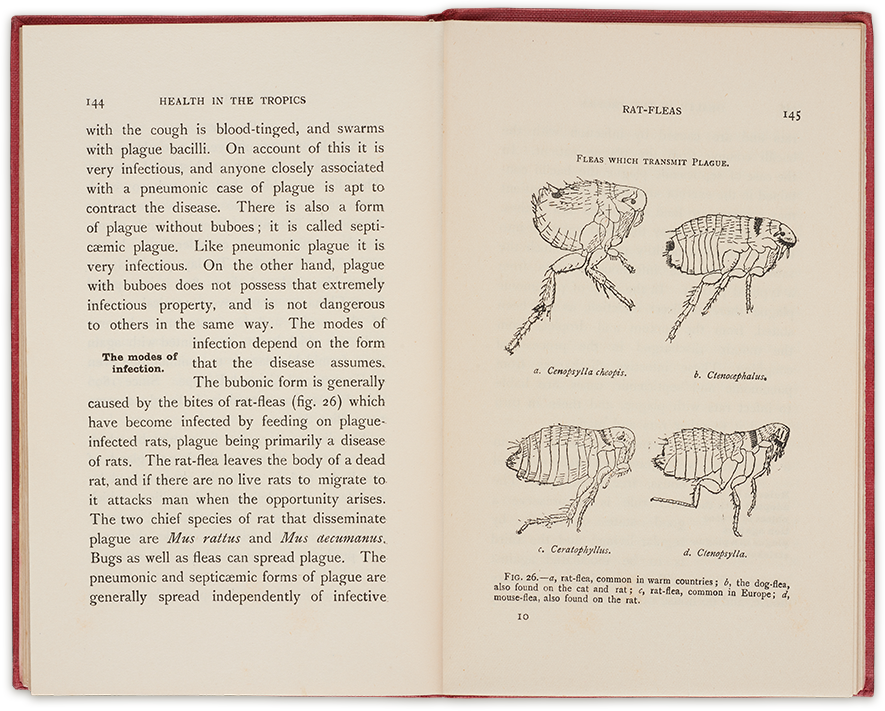

The Maintenance of Health

in the Tropics (2nd edition)

by William John Simpson

In this book, which was first written in 1905, Simpson advises his readers on taking precautions against tropical illnesses such as snakebite, malaria and cholera, among others. He encountered such diseases as the Health Officer for Calcutta in the late 1800s and later in Singapore, where he led an inquiry on tuberculosis in 1906.

1916 | Paper | 19 x 12.5 x 1.6cm

Gift of The Raffles Hotel Museum | 2014-00030

Interestingly, this book was commissioned by the London School of Tropical Medicine, which received financial backing from the colonial office. This was because the turn of the century brought a growing recognition that illness among colonial subjects could affect trade and investment. To protect the metropole, and the increased number of Europeans travelling to the Far East, more funds were finally directed to the serious study of tropical medicine as a discipline.

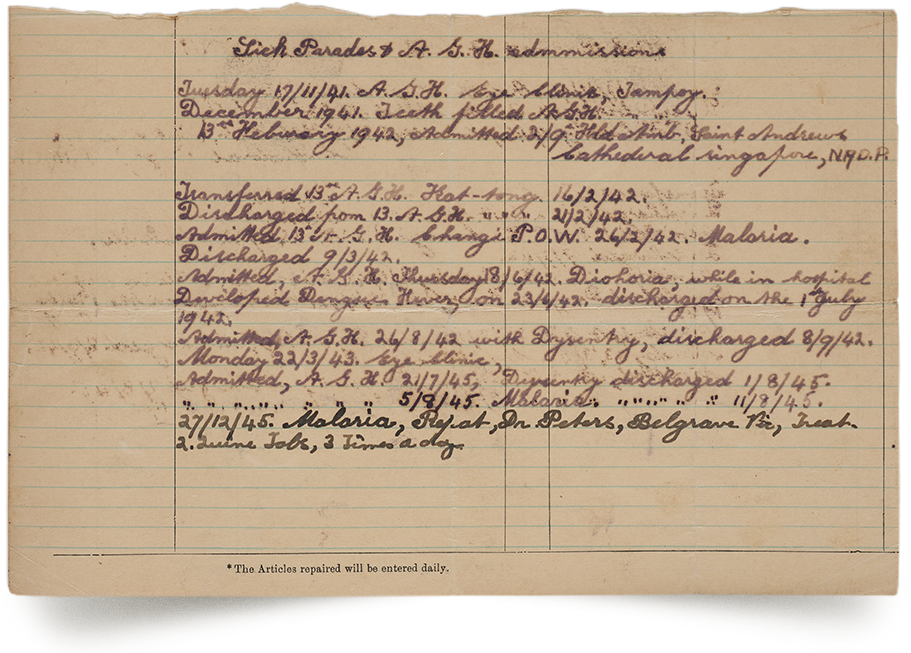

Hospital admission records

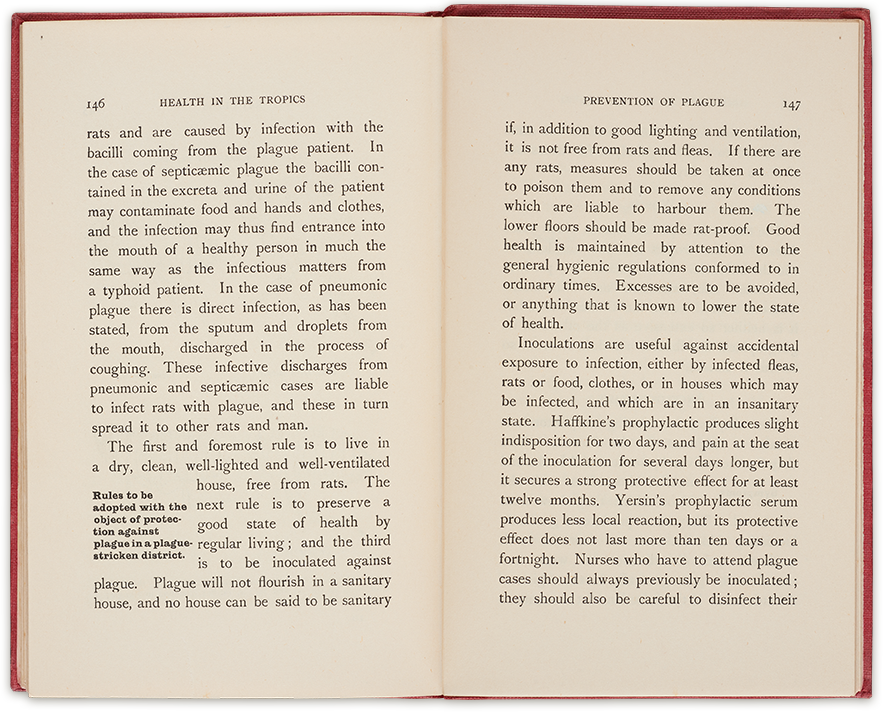

This record of hospital admissions was kept by Sergeant John Ritchie Johnston, an Australian who served with the 2/9th Field Ambulance, one of a number of mobile medical units that treated soldiers on the frontline.

Early 20th century | Postcard | 9.6 x 15.5cm | 2001-03496

Johnston was captured after the fall of Singapore and sent to Changi prison camp. Although he belonged to the medical corps, he was not spared from illness or injury, even being admitted to his own unit at one point. Many prisoners of war suffered from dysentery and malaria, like Johnston, but he was also unlucky enough to have contracted dengue fever while already in hospital.

In addition to writing down his dates of admission and discharge, Johnston also recorded the locations of the field hospitals, providing a unique way of tracking the progress of the Battle of Malaya. His first entry in November 1941 was made when the 13th Australian General Hospital (AGH) was stationed in Tampoi, Johor Bahru. He was then admitted to Saint Andrew's Cathedral before being sent back to 13th AGH, which had by then moved to St Patrick's School in Katong. After the fall of Singapore, the 13th AGH combined with all the other medical units to form Roberts Hospital in Changi.

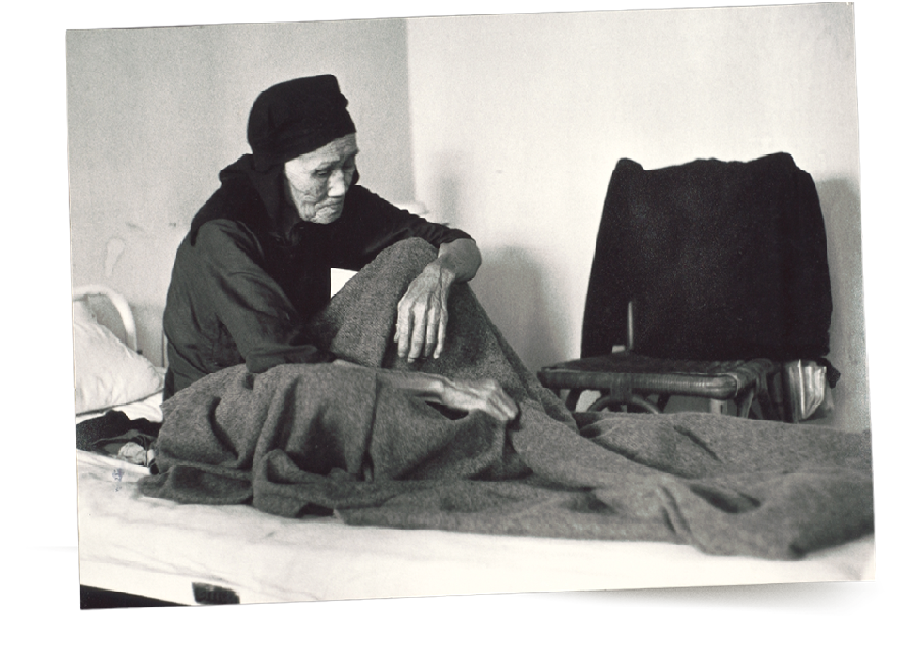

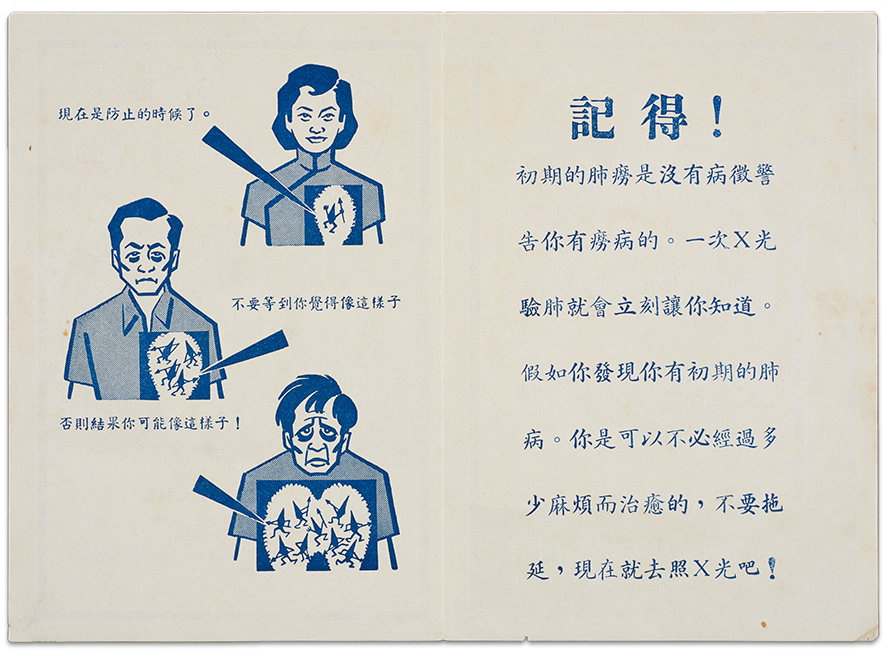

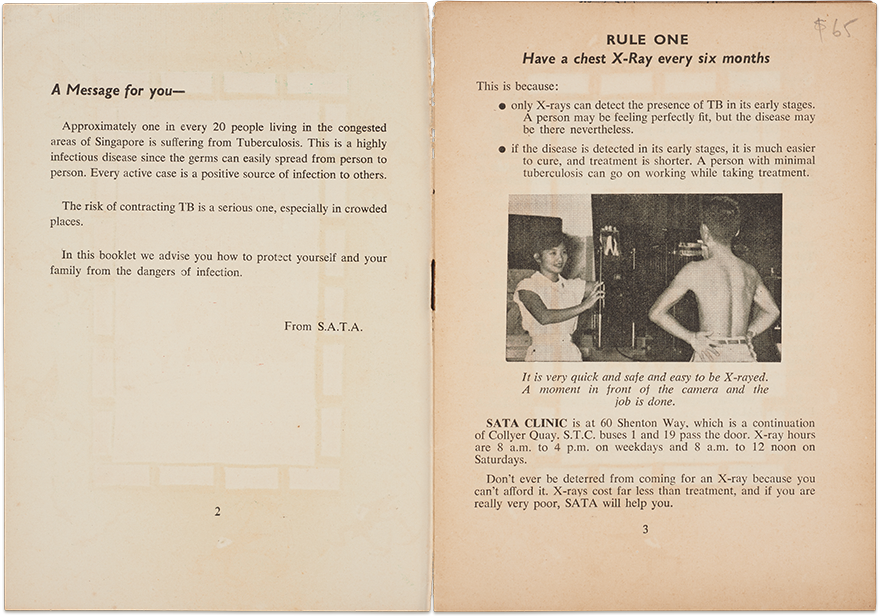

How to Keep TB Away an illustrated booklet reprinted from the SATA Bulletin and published by the Singapore Anti-Tuberculosis Association

This illustrated booklet is an example of how public education was carried out to explain the dangers of tuberculosis (TB), a highly infectious disease that attacks the lungs and can spread to other parts of the body.

1950s−1970s | Paper | 18.2 x 13 x 0.1cm | 2018-00505

It offers five rules to protect oneself and one’s family – having a chest X-ray every six months; keeping the body healthy by consuming a balanced diet; getting a BCG vaccination; using sun, soap and disinfectants to stop germs from spreading; and being clean.

After the end of the Japanese occupation, tuberculosis was a serious problem in Singapore. Over the years, SATA’s team of doctors and professionals continued to provide diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation for people suffering from the disease. By 1960, they had conducted X-rays for more than 250,000 people and detected more than 4,000 tuberculosis cases in a population of 1.6 million.

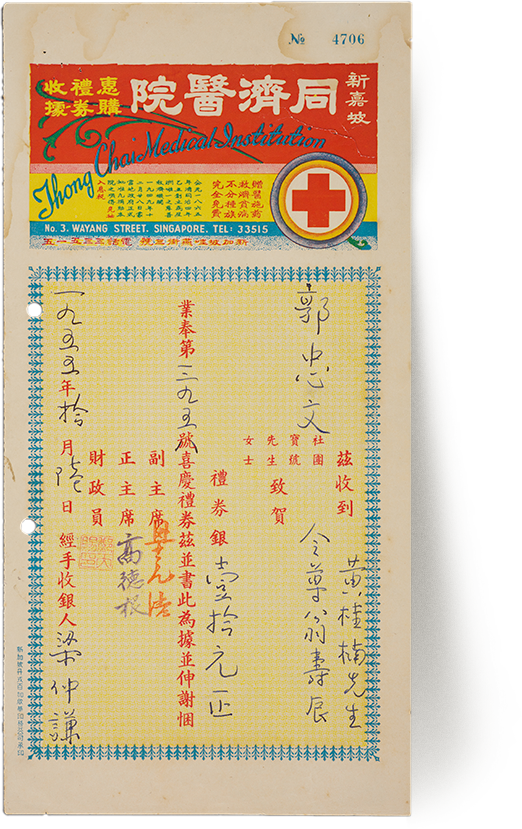

A gift voucher of Thong Chai

Medical Institution

The Thong Chai Medical Institution located on Wayang Street (demolished in 1960) was established to help the poor. Started by a group of migrants from China in 1867, the name Thong Chai Yee Say was derived from the Chinese words “tong” (the same) and “ji” (to help or relieve).

1955 | Paper | 30 x 15.1cm | 2000-00997

It provided free consultations, treatment and herbal medicines for the sick and the needy. In 1892, the group moved to a site granted by the then-Governor Cecil Clementi-Smith and renamed themselves the Thong Chai Medical Institution. In 1960, they moved from their Wayang Street premises to a bigger building modelled after traditional Chinese architecture, which was gazetted in 1973. They subsequently moved to their new building on Chin Swee Road in 1976.

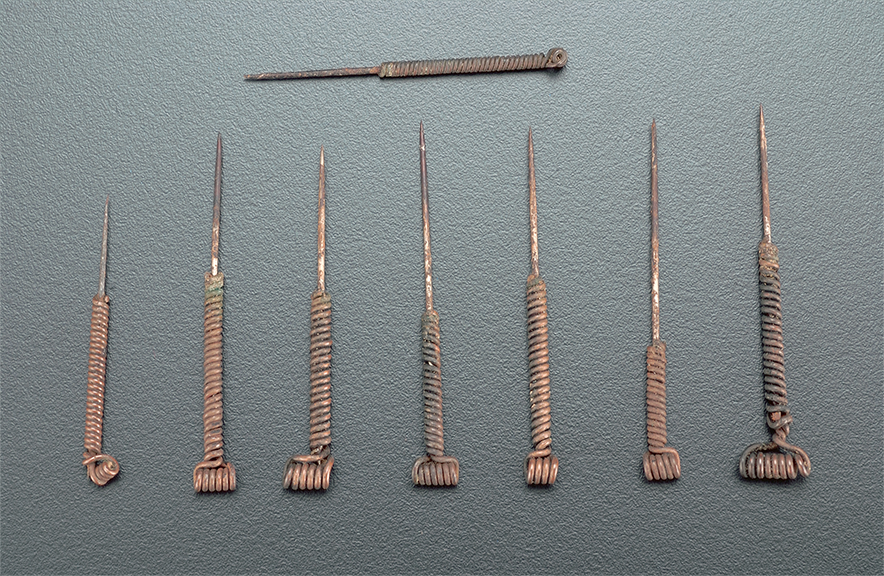

A set of acupuncture needles used in a

traditional Chinese medical hall

Acupuncture is a technique commonly practised in Traditional Chinese Medicine. Needles such as these are inserted into specific meridians in the body to stimulate the flow of life force known as “qi” and to restore balance.

Early to mid-20th century | Metal | 5.0 x 0.5cm | 2001-03086

The technique is used to treat various types of ailments. In addition to inserting the needle, the doctor gently twirls it and sometimes applies electrical pulses.

Packaging for Brand’s Essence of Chicken, UK

The manufacturer’s advice on this Brand’s Essence of Chicken bottle reads: “In case of serious illness and extreme exhaustion it should be given as often as the patient can take it or when prescribed by the doctor.”

Leaflet (multilingual) 24.8 x 22.6cm

Paper box 7.3 x 5.3 x 5.3cm

Bottle 7 x 5 x 5cm

2018-00670-001; -002; -003

The original recipe for Brand’s Essence of Chicken dates to the early 19th century and is attributed to Henderson William Brand, the royal chef in Buckingham Palace in the United Kingdom. To help the ailing King George IV regain his health, Brand devised an essence of chicken drink. In 1835, Brand retired and recreated his recipe for commercial sale to the sick. In 1897, the monarchy issued a Royal Warrant in recognition of the product’s quality. By the 1920s, this well-known tonic began to be sold in Asia where it proved to be a great success as a health supplement. In 1999, the first Brand’s Museum opened in Taiwan.

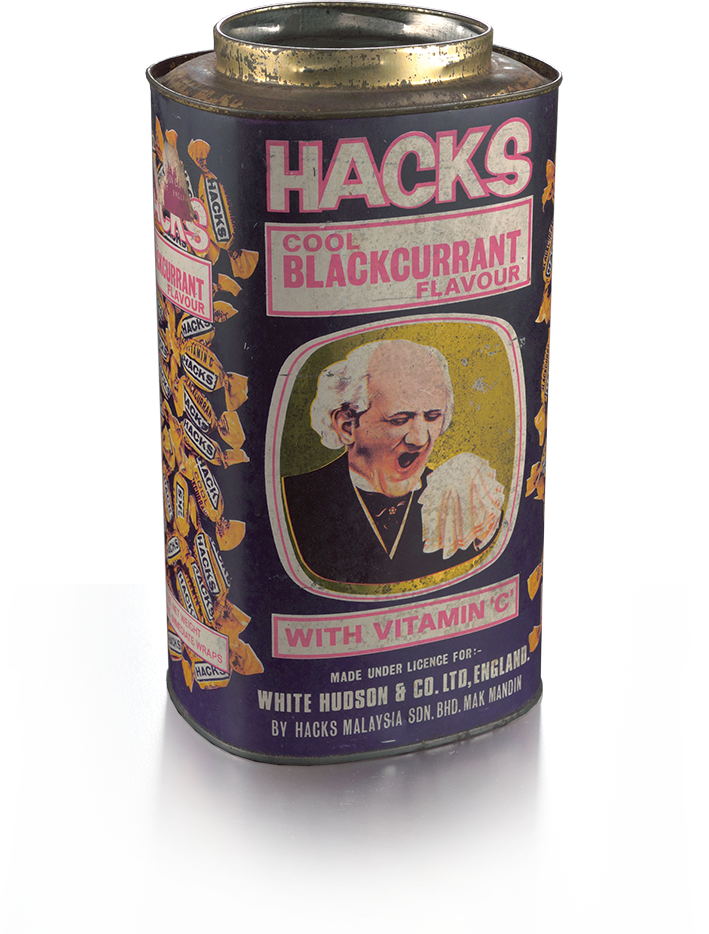

Container for Hacks brand cough drops

“Hacks” medicated sweets and cough mixtures have been produced by the British company White Hudson in Southport, England, since the 1900s. Today, they are world famous.

c1940 | Tin, paper | 27 x 14.9 x 12.6cm | 2007-55034

“Hacks” was first marketed in Singapore in the 1950s. Its sole local agent was Barkath Stores, an Indian Muslim business which gained a name for the brand here. Additional flavours were later introduced.

In 1962, the Singapore High Court granted an injunction restraining a Singapore company, Asian Organisation Limited, from allegedly passing off its “Pecto” medicated cough sweets as “Hacks” medicated cough drops. The “cough sweet row” even went up to the Privy Council in London.

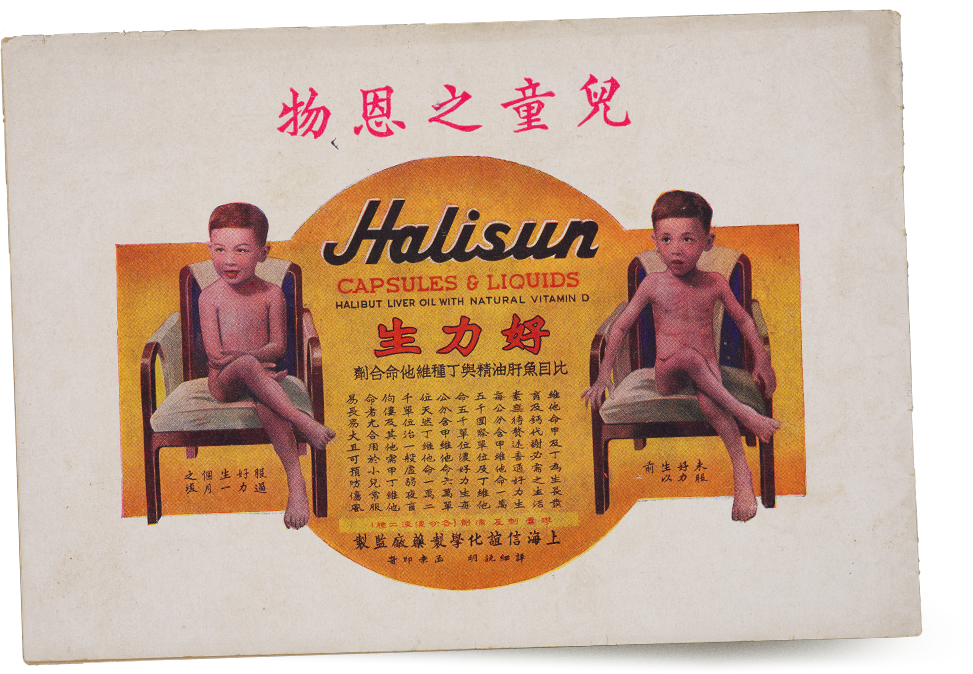

Illustrated booklet in Mandarin with advertisement for Halisun halibut liver oil

This advertisement is sure to bring back childhood memories to many, of consuming some form of fish liver oil as a health supplement. The Halisun halibut liver oil featured here was a brand from Shanghai that came in both capsule and liquid forms.

Mid-20th century | Paper | 18.4 x 12.9 x 0.2cm | 2001-01461

Fish liver oil is believed to be beneficial, especially for children, due to its high levels of omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin A and vitamin D, which help to prevent diseases arising from vitamin deficiencies, such as rickets. The benefits of halibut liver oil are represented on the poster itself, showing a malnourished boy on the right and a healthier version of him on the left, presumably after consuming halibut liver oil over time.

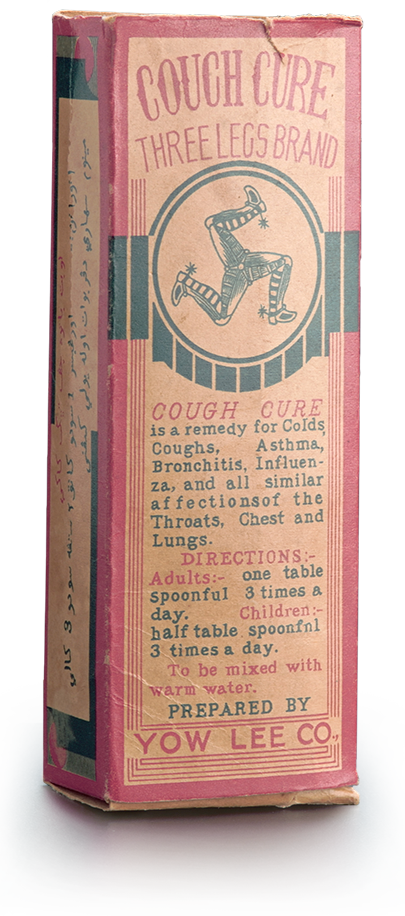

Three Legs brand cough syrupbottle package

This bottle of cough syrup was produced by the Wen Ken Group, a Singapore family-owned Traditional

Chinese Medicine company. Its trademark logo featuring three legs clad in trousers and connected at the

hip illustrate the company’s values of gratitude, trustworthiness and empathy.

1950s−1990s | Paper

12.1 x 4.4 x 2.6cm | 2010-01253

The product is marketed as a cure to illnesses affecting the throat, chest and lungs. Cough syrups such as these usually contain an expectorant to loosen the congestion in the chest and throat caused by a cold. Once the phlegm in the lungs is cleared, the person gets some relief.

Rhyme for taking pulse

This rhyme belonged to a Chinese physician, who was the donor’s father. The document

outlines how taking a patient’s pulse is important to understanding the root of his or her illness. The artefact presented below is currently on display in our Surviving Syonan Gallery.