In 1959, health inspectors and radio police desperately tried to search for an infant’s father – a taxi driver – at the centre of a smallpox outbreak in Singapore, but to no avail. Revealing the practice of contact tracing, a newspaper article titled “25 Contacts of Sick Baby go into Quarantine” reports how despite the threat of smallpox, many people still did not get the free vaccinations that were being provided by the government at the time.

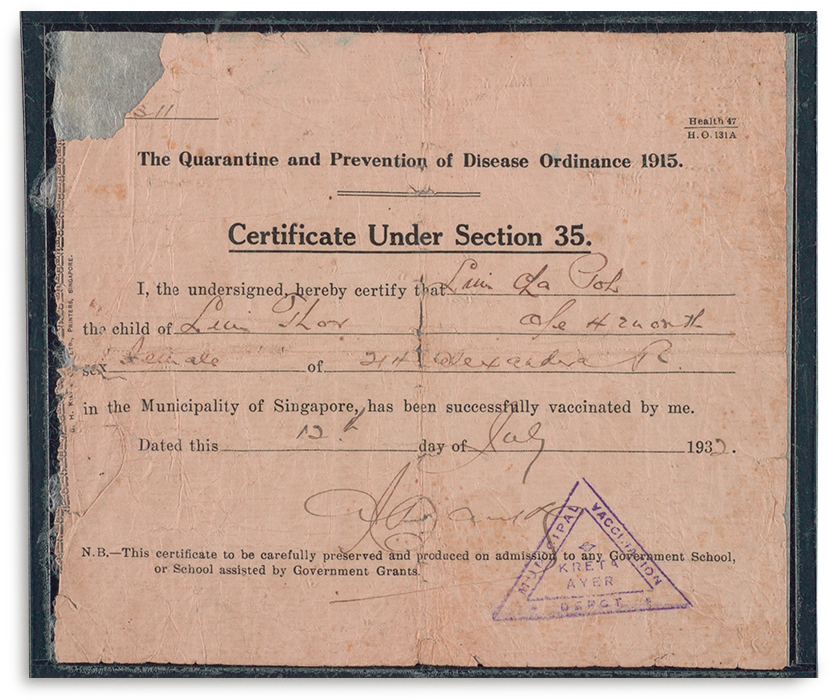

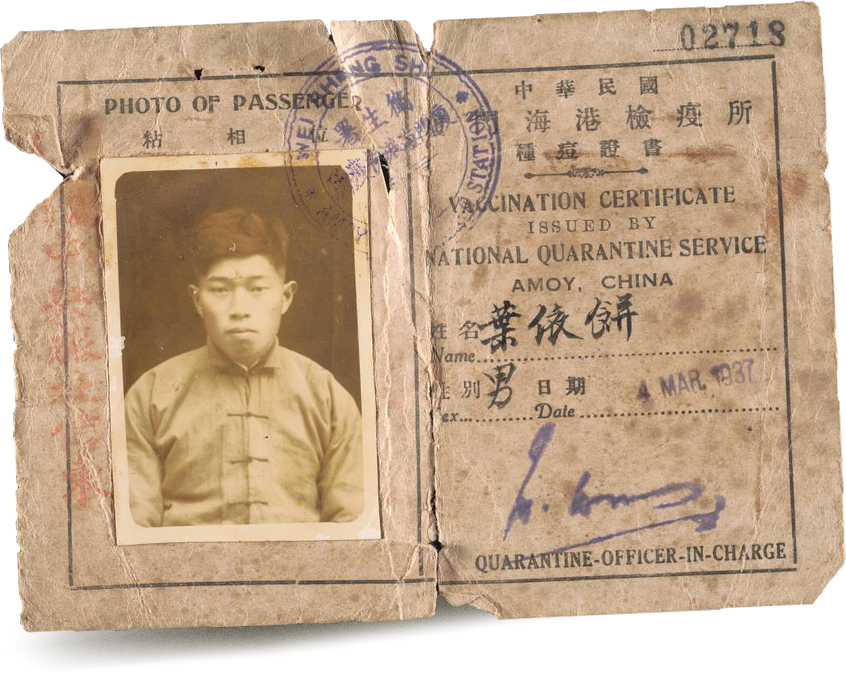

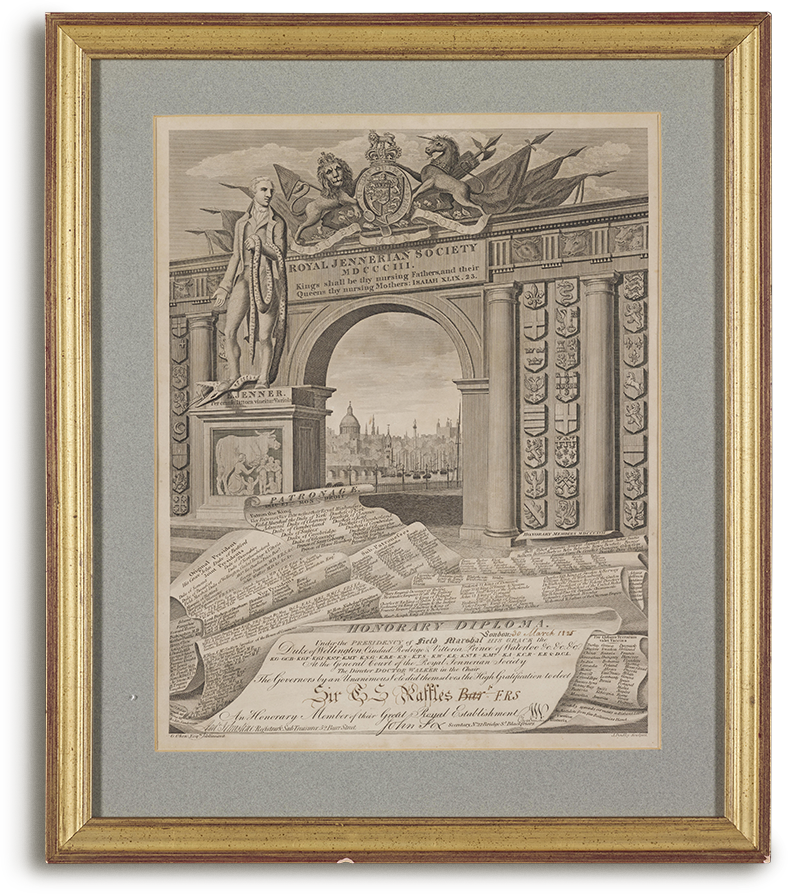

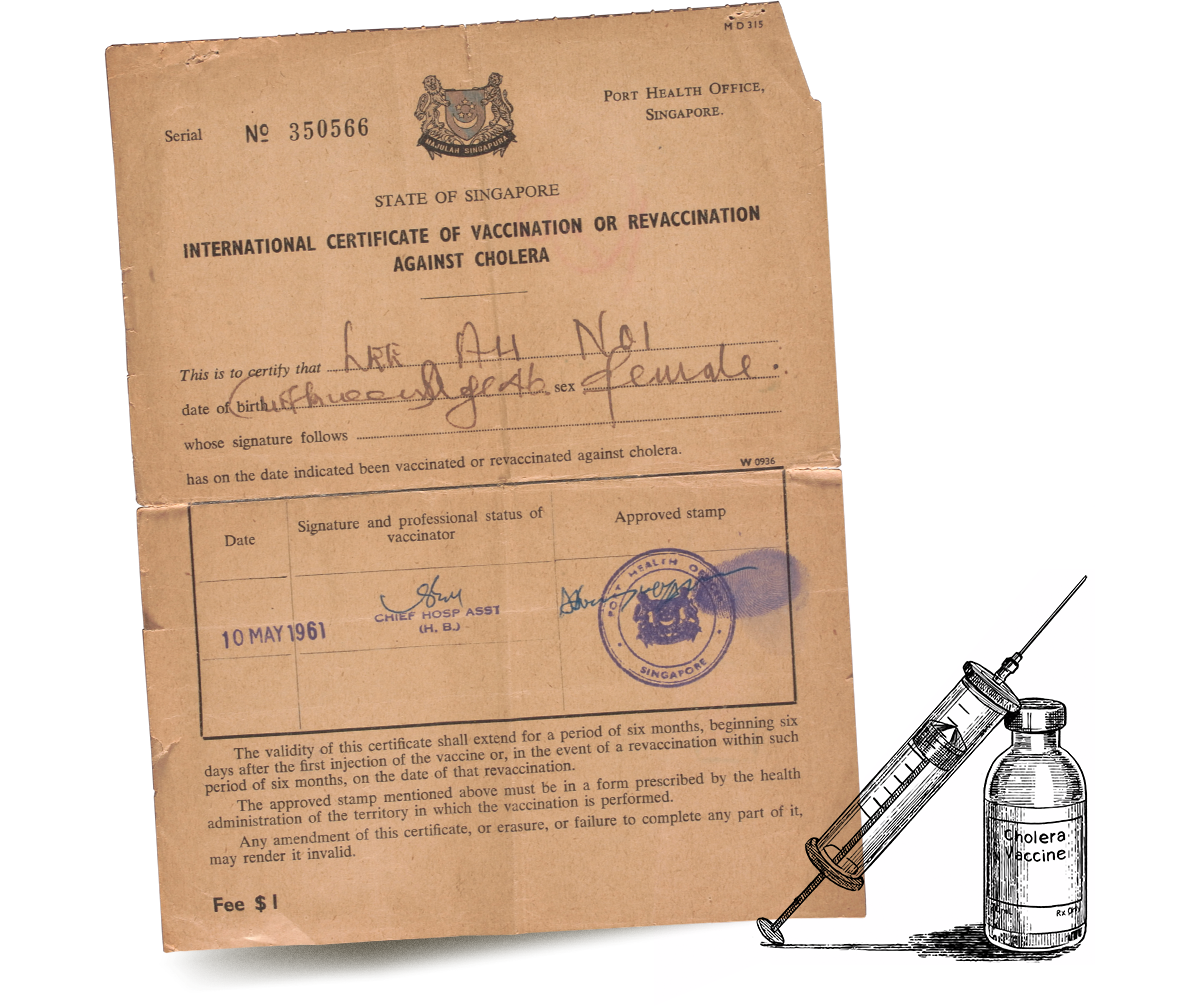

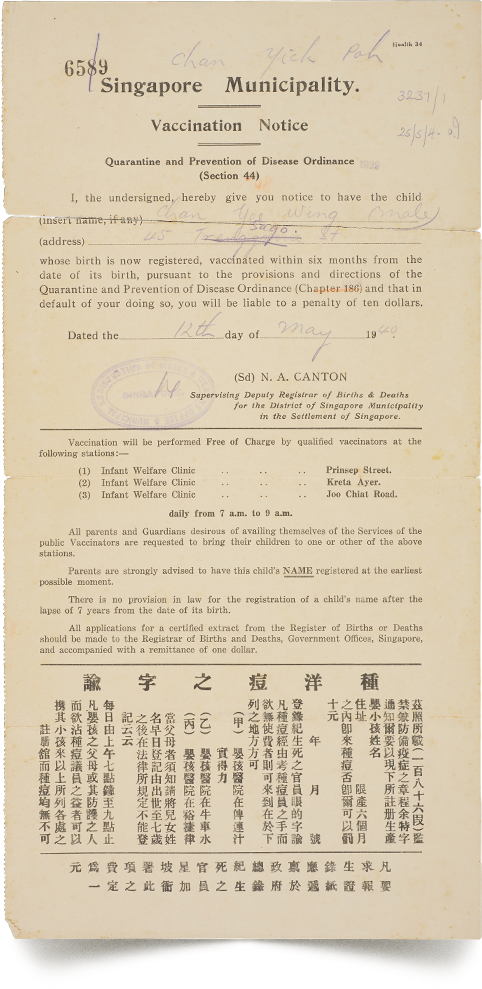

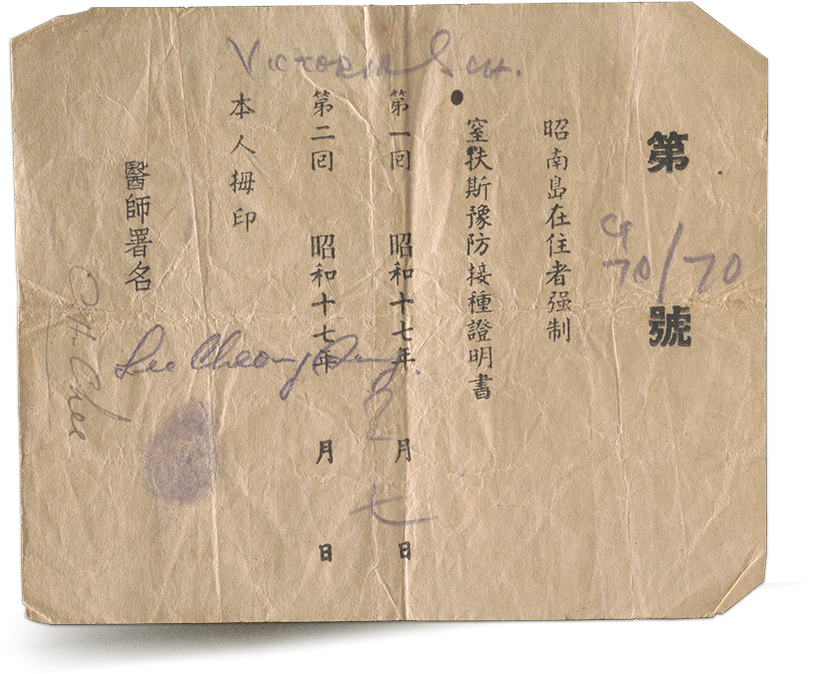

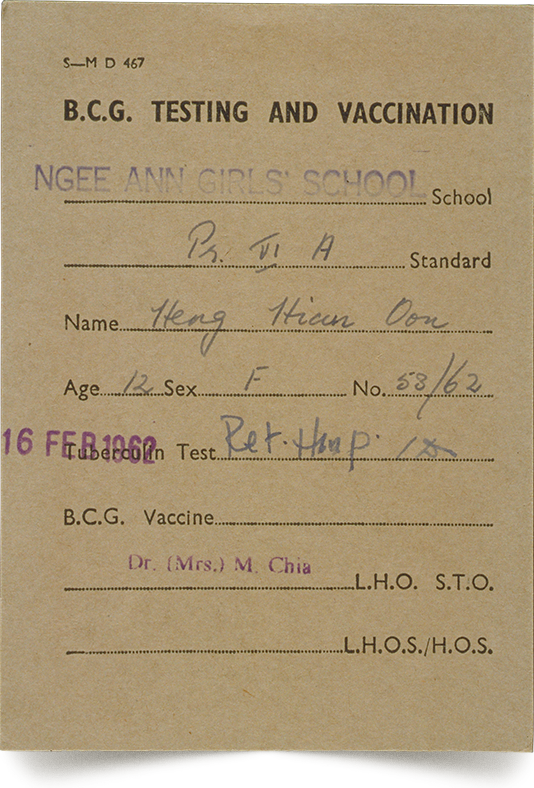

This section features several artefacts and documents related to vaccination practices

and policies in Singapore over the years.